Class 37: The Great Stereopticon, Session 3, the Movies. Hollywood – Living the Dream

You can listen to a podcast of this lecture at https://www.spreaker.com/user/youngfaithradio/osc-class-37

Introduction: Going through a pile of CD’s at home a few years ago, I found a collection of songs sung by Judy Garland, an American movie actress best known for her role as Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, the one actress more than any other whose onscreen persona typified 20th century America’s image of “the girl next door.” The program notes summarized her biography and ended with the words, “She lived the dream we all want to live.” The curious thing is that the previous paragraph had ended with relating the circumstances of Garland’s death at age 47 from a drug overdose, and that the mini-biography had not omitted tragic details of her personal life from the time she became an “asset” of MGM as a young teenager: self-loathing, drug addiction, multiple failed marriages, and so forth. When one does a little further reading, one also finds adultery and abortion at an early age. We do not know if Judy Garland intended to kill herself the night she died – it seems to have been an unintentional overdose. But she certainly killed herself, first spiritually and finally physically, by the way she chose to live. But that’s all right. After all, she “lived the dream we all want to live.” What more could one want?

Recall the opening premise of this entire section of our course: The goal of the global elite is to create a new kind of human being, to “redefine what it means to be human.” Cinema, the defining art form of the 20th century, literally a “Great Stereopticon,” has by now so radically reshaped – that is, deformed – the average person’s idea of normality, of morality, of humanity, of the very purpose and meaning of life, that one could say that this goal of redefining humanity has more or less been accomplished in the minds of the overwhelming majority of people living in the “developed world.” To most of the people living around us, what goes on in movies or television shows or YouTube videos is the really real – it is more real and more interesting than their own lives, far more compelling than the true good of the people they claim they love. They may not like or agree with everything they see on the screen, but they cannot pull themselves away. It is a Fatal Attraction.

Cinema, of course, wields far more power than the newspapers or the radio. It retains the newspaper’s appeal of vulgarity and superficial thought masquerading as wisdom, and it retains the power of radio, the power of the spoken voice. It also projects the primordial power of theater, the Dionysian mystagogy we talked about last time. And, added to all this, taking the power of all of these things we’ve already talked about quantum leaps higher to a level never seen before, cinema overwhelms the mind with stunning, captivating and enthralling visual images, along with powerful music and sound effects. It constitutes a rich ensemble of so many different art forms, combined with so much power and effect, that one can say with great confidence that never before was there anything like this. And with few exceptions, the virtually irresistible might of this impossibly, heartbreakingly attractive thing, this pancratic psychological super-weapon that enslaves millions of souls over one weekend without anyone firing a shot – the power of this awesome thing has always been, and remains, for the most part, under the domination of men who hate God, hate Christ, hate the Church, hate us, and want to destroy us – men who serve the Devil as their god. If we don’t understand this, we don’t understand what the movie industry is all about.

At this point, I need to disclose something. Probably like most of you listening to me right now, I like movies, especially older movies with absolutely no computer generated graphics, and with good writing and good acting, and in particular cinematic presentations of intelligent stage dramas or screenplays based on great literature. But because I like it so much, because it leaves such a deep impression on me, I rarely indulge in it, and when I do, it is for the most part with a very short list of plays or movies that are fairly innocent, or, if they depict evil, render a genuinely moral judgment, and that I have watched repeatedly over many years, because I am really afraid to venture out and watch anything else. It is precisely because we like it so much, because it leaves such a deep impression on us, that we must be so careful.

My point in saying all this is that I am not standing on some Orthodox version of an Olympus of hopelessly untouchable perfection, hurling down thunderbolts and saying, “If you ever watch a movie, you are evil, and you are doomed!” That would be hypocritical, and, worse, it would be a mistake, because it would not motivate you to take realistic survival steps to deal with this powerful thing, and survival is what we are all about here. Let’s all recall that Orthodox spiritual life is about reality. We are supposed to be cleansing our minds and hearts of delusion and seeing things as they really are. How much time do we spend cleansing our minds of delusion, and how much time do we spend luxuriating in delusions? Yes, we are not consecrated hesychasts, and there is room for art in life, and great art can lift us above the banality of daily life and pierce our hearts with the joy of what is universally good, true, and beautiful. It can lead us to God. But how much theater, cinema, television, and so forth is really this kind of art? How much prayer and thought do we really put into discerning which selections of this mental food truly help us and our loved ones, which of them are at best a waste of time, and which are spiritually poisonous? Let’s be honest.

We could do an entire “Survival Course” just about movies. Maybe we should at some time in future. In this short lecture, I can only hope to cover a few sub-topics relating to cinema and offer a few practical suggestions. My approach in this lecture is to examine cinema in the “good old days” of the heyday of the “Silver Screen” and not address the problems with the medium that have developed since then. We might think that the problems with movies started with the cultural revolution of the 1960’s, when drugs, sex, and rock n’ roll took over American – and then world – culture, and that all the movies from the “good old days” are innocent, but this is not true. To understand any new historical development, including an art form, one must start at the beginning, and usually the dominant and permanent characteristics of any enduring historical reality are present at the beginning and easiest to observe at that point. We cannot begin to develop our Orthodox lens to understand cinema by starting with movies produced in this decade of the 21st century. They are too close to us, and the problems are both extreme and constantly changing. Our reaction would be just that – a reaction – to a kaleidoscopic and incomprehensible barrage of fragmentary impressions flung at us by extremely advanced media technology. Let’s go back in time to the 1920’s through the 1950’s and try to understand the underlying nature of cinema in order to create the understanding we need to deal with it as it exists today. I am going to talk about cinema from an American point of view, not only because I am in the United States and most of our audience are Americans, but also because cinema, like a lot of 20th century cultural movements, was basically cooked up in the laboratory of 20th century America and then spewed out to the rest of the world. Movie culture is the phony culture that replaced historic American culture and then became the world culture.

I. This really is the Great Stereopticon

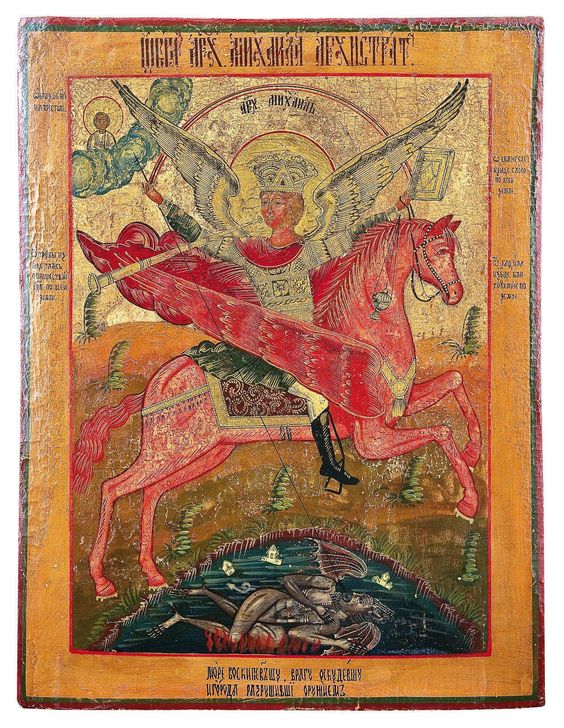

Our guiding image of the “Great Stereopticon,” that apt expression borrowed from Richard Weaver, refers to the traveling “magic lantern” shows of 19th century America, in which a projectionist could transport simple, rural people to faraway times and places by the “magic” of colorful images thrown on a wall accompanied by a captivating story line. The cinema is, of course, the magic lantern “on steroids.” We are so jaded today with television, movies, and Internet video – YouTube and so forth at the touch of a finger on a personal “device” – we cannot imagine how overwhelmed people were in the 1920’s or 1930’s, sitting in a large, darkened auditorium and looking at a vast screen on which impossibly attractive – or impossibly repulsive – people far larger than life-size engaged in various adventures of violence and romance, or sang or told jokes. Probably the only way to understand how they felt is if you went off to a monastery for a year, a strict monastery that limited communications media to a telephone and a computer in the abbot’s office, and where all you did for weeks was pray, worship, do manual labor, read, have simple conversations, and deal with plants and animals. Then, when the year was up, you would come back to the “real” (i.e., unreal) world and go on a video binge, watching movies and TV shows on a giant screen all day on the very first day you came back. The shock would, perhaps, approximate what those people felt back when movies first came out. You would be overwhelmed; the attraction of the thing, no matter how much disgust you felt, would feel irresistible. You would realize, perhaps for the first time, how powerful it really is, and how its unreality posing as reality can so rapidly replace the real things in your mind and soul that you had acquired and treasured up during your year in the monastery. This is more or less what movies did to our forbears in the first half of the twentieth century. A false vision of life replaced the examples of normal life, much less the examples of a holy life, as their paradigm for how to think, talk, and behave.

II. Creating the New Normal

From its beginning, the movie industry set out to create a new self-image for the American people. Today, of course, what is presented as normal in the movies is often unbelievably bizarre, utterly inhuman, and overtly demonic, far beyond anything seen in the 1930’s. But the old movies did enormous damage to the American character from the beginning, by convincing ordinary people that their received way of life, based on church, family, ethnicity, and local community, was uninteresting and contemptible, and that to be “someone” they must start imitating the kind of character and the kind of society glorified on the screen. Sometimes the attack on traditional culture was overt. More often it was disguised: the “good old ways” are presented in a sentimental, superficial fashion that seems to praise them but subtly trivializes them, and the hero or heroine transcends the old life by breaking old ties and embarking on a new, more exciting way of life. There are numerous themes that we could explore here, but I’ll address three of them: big city life as the new normal, the revolution in domestic mores, and the fascination with criminality.

Until World War II, most Americans still lived in small towns or farming communities, and most lived as members of extended families and local cultures that were, by today’s standards, almost unbelievably homogeneous in race, language, and religion. Even in the big cities, immigrant communities lived in tight-knit neighborhoods conceived on a human scale, centered on family life and, most often, Roman Catholic parish institutions – church, school, and social organizations – designed to preserve both religious and ethnic identity.

If a visitor from “another planet,” as the expression goes, learned about 1930’s America only from watching movies, however, he would conclude that the paradigmatic American was a deracinated, lonely, irreligious, restless, iconoclastic, fast-talking, and fast-living denizen of New York or Chicago, and that his life consisted of the pursuit of money, power, and love affairs. He would deduce that nearly all American women are impossibly beautiful, that they all dress and comport themselves as prostitutes, and that they all smoke cigarettes. He would observe that the small town or the old ethnic neighborhood, and family life, when they are portrayed, are presented – even when they are depicted lovingly – as a situation to be escaped from or grown out of, in order to live the cosmopolitan life of the big city, and to live for oneself or for one’s romantic love interest.

I know that one can excessively idealize small town and rural life – of course they were never perfect in any nation, including Orthodox nations, because everyone is sinful. Real life is always beset by the passions of those who are living that life, and by the demons. We all know that. But it is also undeniable that God’s plan for the temporal social order, in order to make man’s eternal purpose more attainable for ordinary people, is based on the life of the nuclear and extended families, and of small, local, stable, communities of people sharing one faith, one language, one ethnicity, and one culture, who are born, live, and die in the same place, often on the same piece of land, even in the same house. This is just normal human life; this is what enables the stability and wholeness of the psyche that forms the best starting point for the life of the spirit. (The fact that my simply saying this in 2019 can get me accused – even, sad to say, by some Orthodox people – of intolerance, “racism,” and a variety of other ideological thought-crimes, shows how completely insane our life has become.)

This normal human life in the small town or on the farm is lived at a slow pace, and it does not encourage competition or aggression, and therefore it creates a patient, gentle character not inclined to arrogance or boasting, and generally open to the goodness of life. The cosmopolitan life, on the other hand, lived in an atmosphere of hurry and aggression, of endless competition, creates a nervous, unstable “smart aleck” character given to wisecracking remarks, arrogance, and cynicism. (We can see a comic caricature of this in the “Three Stooges” characters, for example.) In general, we can say that the big city life makes for a hardening and coarsening of character, even in people who intend to be moral and good. It lowers the tone of life and deflects man from his proper temporal purposes and, above all, from his eternal destiny.

But the small town American watching a movie in the 1930’s saw this lower, coarser kind of life presented as glamorous and desirable. It created in his mind a “new normal”. And along with the big city life presented as normal, came, of course, the sexual revolution. Even when an old fashioned romantic movie ends in a wedding, usually the hero and heroine have already behaved in ways that, to be polite, fall short of the standards of the Church. Also, the emphasis is not at all on marriage as a sacred or social institution involving duty and self-sacrifice, but on marriage as a form of romantic love affair with constant sexual overtones. This by itself, even if actual fornication or adultery are never condoned in a given story, is a fatal derogation from the traditional paradigm of marriage regarded primarily as the essential social institution, involving sacred social and intergenerational moral and legal obligations, not even to mention a derogation from the higher and distinctly ascetic demands of the Church’s sacramental marriage.

Getting back to poor Judy Garland: One of her lesser known movies presents a perfect stereotype for the purely romantic marriage as the cinematic norm. It’s called The Clock. Today it would be called a “chick flick,” and to our jaded 21st century sensibilities it could appear as hopelessly charming and innocent. It is not innocent, however; it is terrible. It depicts just about everything I’ve talked about: marriage seen almost entirely as a romantic adventure, the unnatural speed of city of life, deracination, a condescending sentimentalization of family life and religion, and so forth. You can read the plot summary at the Wikipedia article (yes, I think we can trust Wikipedia this far, to summarize absurd movie plots) at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Clock_(1945_film) .

So what do we see here? Two strangers (in New York, of course) meet and get married within 48 hours. There is a nod to family life – the milkman and his wife are a “normal” foil to the main characters’ fevered instability. There is a nod to “religion” – the heroine wants to kneel in a church and recite their vows again to “feel married.” The sentimental churchgoer who wants to feel good about enjoying the movie can say, “You see, those good old movies showed people who ‘believe in God’!” But obviously the movie presents an anarchic and dangerous understanding of marriage. The protagonists are completely severed from traditional loyalties and act as isolated individuals, little lost souls clinging to each other in the impersonal world of cosmopolitan modernity. They make this incredibly important decision based on sexual attraction and romantic emotion without any reference to their parents, to religious or social duty, or the long-term consequences of their decision. And this entire modern big city fairy tale also carries the sanction of the “Good War,” for by 1945 Americans have been brainwashed to believe that their country’s part in World War II was some kind of holy crusade, and, more importantly, that the social havoc created by the war and the new kind of society that emerged from it was also “holy,” was a progression to something higher and better than that Mom and Pop life before the great social experiment the war somehow justified. Before the war, a teenage Judy Garland, playing opposite Mickey Rooney in the Andy Hardy movies, typified the “girl next door” of small town life and loves. Now Judy – and America – have “grown up” in that great social engineering experiment known as World War II, and she is the girl next door no more, but the completely chimerical and insubstantial glamor girl of the “Greatest Generation” – someone who is attractive precisely because she is not familiar but foreign. The small town young woman says, “I want to be like that!” and the small town young man says, “I want a girl like that!” This is the generation that gave birth to and raised the Baby Boomers, my generation – arguably the most selfish and despicable generation in American history. Our parents, who were the young people watching The Clock in 1945 down at the main street movie theater, still believed in faithful love and marriage, and having children, and going to church, and being involved in a law-abiding community. But their image of all these things was profoundly deformed by Hollywood, and this false image seriously damaged their lives and affected how they reared their children.

Besides creating a false idea of family and marriage, Hollywood also glamorized criminal behavior. In his The Crisis of Our Age, Pitirim Sorokin points to the rise in the genre of crime literature – cops and robbers tales, detective stories, and so forth – as a mark of a corrupt, dying culture. Movies took this and ran with it. Even when the gangster characters played by James Cagney or Edgar G. Robinson “get what’s coming to them” in the end, they still seem somehow attractive in their very villainousness, they are more real, more alive, somehow, than one’s law abiding parents or teachers or pastor. The criminal subculture plays an inherent role in the very attractiveness of big city life – its fevered pace, the feeling of “living on the edge,” the seduction of danger.

We could go on and on, of course. Perhaps we should continue this subject of the movies in our next talk. But for now, what about some “survival tips”? Here is a short list.

1. Constantly remind yourself that movies are very powerful and, if you must watch them, be very careful about what you choose, and be very critical of what you see. An Orthodox Christian should never just run down to the video store or go to the theater to watch the latest offering “just because.”

2. Don’t immerse yourself in movie or TV culture. It should be an occasional diversion, not a daily aspect of life.

3. Dignified cinematic productions based on truly great literature or classic drama are to be preferred.

Let’s live real lives, and not try to “live the dream”!